N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]

Inheritance go brrrrrrrr... abusing turing-complete typesystems to write fun programs in Python.

Types are cool! But y'know what's even cooler? A CTF challenge on types!

This year's MapleCTF graced us with a challenge involving much class, much inheritance, much confuzzlement, and much eyesore.

Description

Mostly Harmless

Some people consider type annotations to be useless. I consider everything but type annotations redundant.

Author: JJ

17/291 solves.

The chal is also humorously tagged "cursed" and "misc". Well, that's reassuring...

Anyway, we're presented with two files:

app.py: Driver code to convert the flag (input) to a mysterious line of output, then opens a subprocess and runsmypy output.pyoutput.py: A template file full of class declarations and inheritance. Utter gibberish on first sight.

You can follow along by getting these files here.

Solve

What? A section titled "solve"? Already? What about the usual analysis and observations?

Usually I begin my writeups with an extensive analysis section. Contrary to this, Mostly Harmless is one of those blursed challenges which favours those with strong guess-fu; but the challenge is so intellectually challenging and deep, that to properly reverse (let alone understand) it would take a PhD, years, extra study post-CTF.

The key idea is to recognise:

- How does the flag checking work? Where is the final condition which decides whether the input is correct or not?

- By using the mypy type checker.

- How do the classes containing numbers (e.g.

QLW_s1,QRW_s1) relate to the classes containing a letter (e.g.L_x,L_a)?- By inheriting classes in a specific manner, therefore creating a subtyping relationship.

Still, let's look at some key insights:

The final line of

output.pyis built by stacking input in a recursive fashion:L_<INPUT[i]>[N[ L_<INPUT[i-1]>[N[ ... ]] ]]- Thus, characters are encoded by the

L_*classes. - The chain also begins (or ends?) with

QRW_s29.

- Thus, characters are encoded by the

There are a bunch of

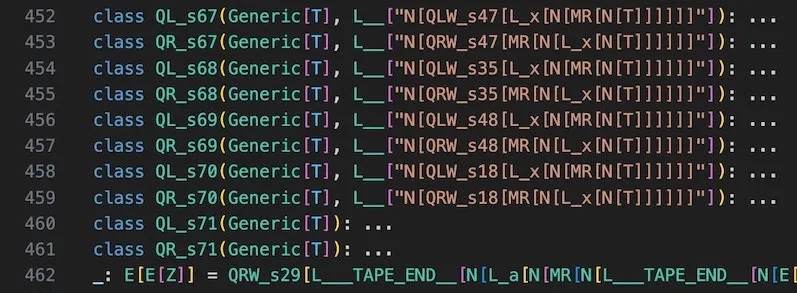

Q*_s*classes, numbered from 1 to 71. Indices, perhaps? Or just references?Any clue to the relationship between these symbols? Yes! We see interesting stuff from lines 320 to 459.

# Line 378. class QL_s29(Generic[T], L_n["N[QLW_s31[L_x[N[MR[N[T]]]]]]"]): ... # │ │ │ # │ │ └── Next number # │ └── Next letter in flag # └── Current number

And guess what? That's all we need! Just follow the numbers like how Alice follows the White Rabbit!

Script

The solve is rather simple and fits within 25 lines (including comments!).

import re

# Extract the lines containing pointers(?)/relationships between letters.

with open('output.py') as f:

lines = f.readlines()[319:458:2] # Skip every 2 lines, bc redundant info.

lookup = {}

# Parse and store the relationships in a lookup map.

for line in lines:

curr_idx, char, next_idx = re.findall(r'Q._s(\d+)[^ ]+, L_(\w).*.W_s(\d+)', line)[0]

lookup[int(curr_idx)] = (int(next_idx), char)

# Follow the pointers until we hit 71.

idx = 29

flag = ''

while idx != 71:

idx, c = lookup[idx]

flag += c

# Profit!

print(f'maple{{{flag}}}')Flag

Lé Flaggo

maple{no_type_system_is_safe_from_pl_grads_with_too_much_time_on_their_hands}C++ template metaprogramming reverse when?

We're done. We got the flag. But my curious side wants to dig deeper.

So let's go deeper! The rest of this post attempts to dissect the type theory behind the challenge, starting from basic principles.

Back to the Basics

This section attempts to bolster the reader's understanding of programming and type theory in order to understand the nitty-gritty of the challenge. If you're comfortable with types and variance, feel free to skip to the next section. If you have any questions, do let me know.

Classes

Classes are a fundamental concept in object-oriented programming (OOP) that allow us to define objects with attributes (variables) and behaviours (methods/functions). They serve as blueprints or templates for creating instances of objects. In the functional realm, classes are used to create new types.

From here on, class and type are interchangeable.

Here's an example:

# Declare a new class called Challenge.

class Challenge:

# __init__ is a magic method called automatically when an instance is created.

def __init__(self, title, description):

print(f"Creating challenge {title}...")

self.title = title

self.description = description

# Create instance of our class.

chal = Challenge("Mostly Harmless", "A totally harmless reverse challenge abusing Python types.")

# Prints "Creating challenge Mostly Harmless..."But we'll stay relevant to the challenge and keep things simple by declaring classes without a meaningful body. Let's not worry about fancy Python methods and class mechanics.

# This also declares a class called Challenge.

class Challenge: ...The ... (ellipsis) usually denotes an empty implementation.

Classes can do a lot more, but for now this explanation suffices.

Inheritance

Inheritance is a mechanism in OOP that allows a class to inherit attributes and behaviour from another class. The new class is called a subclass or derived class, and the class being inherited from is called the superclass or base class.

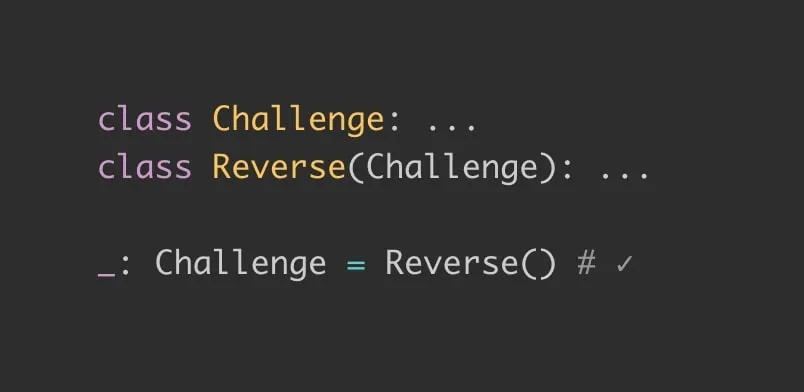

class Reverse(Challenge): ...Here, Reverse is a subclass of Challenge, and Challenge is a superclass of Reverse.

Semantically, a

Reverseis also aChallenge, but the inverse does not always apply.assert isinstance(Reverse(), Reverse) == True # A Reverse is a Reverse. (Duh.) assert isinstance(Reverse(), Challenge) == True # A Reverse is also a Challenge. assert isinstance(Challenge(), Reverse) == False # Supertype is not a subtype.Type-wise, it creates a relationship:

Reverseis a subtype ofChallenge. More on this later.

We can inherit multiple classes too:

# Create a class for Python Reverse challenges.

class PythonReverse(Python, Reverse): ...Both Python and Reverse are superclasses/supertypes of PythonReverse.

Mathematically, we denote inheritance with $A : B$, where $A$ is the subtype and $B$ the supertype.

Typing

Python is a dynamically-typed language and does not offer type-checking out-of-the-box. This challenge uses the third-party tool mypy to type-check output.py (get it with pip install mypy). Let's look at a typed example.

class Challenge: ...

class Reverse(Challenge): ...

class Web(Challenge): ...

x: Challenge = Challenge()

y: Challenge = Reverse()

z: Challenge = Web()We declare three classes:

Challenge,Reverse, andWeb. The latter two are nominal subtypes ofChallenge.Nominal vs. Structural Subtyping

Generally, there are two ways to look at subtypes:

Nominal Subtyping: Two types are considered subtypes if they were declared such. Usually an explicit link is specified, e.g. inheritance.

class Reverse(Challenge): ...Here,

Reverseis a (nominal) subtype ofChallenge.Structural Subtyping: Two types are considered subtypes if their structures match. No explicit linking required.

class Challenge: title = ... description = ... def print(): ... class Web: # No inheritance. title = ... description = ... url = ... def print(): ... def instantiate(): ...Webis a (structural) subtype ofChallenge, becauseWebcontains attributes and behaviour ofChallenge.This is more akin to duck typing.

All the subtyping discussed in this post is nominal subtyping.

We then...

- declare three variables

x,y,z, - annotate them with

Challenge, and - initiate them to instances of the classes we created.

- declare three variables

Beware, Challenge takes on two roles here:

- Type. When inheriting (in the declaration of

class Reverse) or when annotatingx,Challengeis treated as a type. - Constructor. When calling

Challenge(), we are instantiating an object.

The type annotation is a constraint we place on the variable.

When we run mypy on this file, the type-checker will:

- process class declarations,

- register subtyping relationships ($\texttt{Reverse} <: \texttt{Challenge}$, $\texttt{Web} <: \texttt{Challenge}$), and

- type-check annotations and values.

- $U <: T$ denotes "$U$ is a subtype of $T$".

- $U :> T$ denotes "$U$ is a supertype of $T$".

Examples

- $\texttt{int} <: \texttt{object}$

- $\texttt{RuntimeError} <: \texttt{Exception} <: \texttt{BaseException}$

- $\texttt{object} :> \texttt{int}$

The type-check passes if the values are subtypes of the annotations. This is also called a subtype query (distinguished by $<:^?$).1 Other examples of subtype queries:

x: int = 5 # Is type(5) a subtype of int? ✓

y: float = "abc" # Is type("abc") a subtype of float? ✗

z: Challenge = Reverse() # Is type(Reverse()) a subtype of Challenge? ✓We'll find out later how to resolve subtype queries. That is, we'll look at how to figure out if a class is a subtype of another class. (Jump.)

Subtypes are great for polymorphism as they allow us to construct containers (lists, arrays, maps) in a concise and type-safe manner. Here's a simple example:

from typing import *

class Challenge: ...

class Reverse(Challenge): ...

class Web(Challenge): ...

class Pwn(Challenge): ...

# Create a list of different challenges.

chals: List[Challenge] = [Reverse(), Web(), Pwn()]Invariance, Covariance, and Contravariance

Wow, big mathy terms.

Suppose we want to display our list of challenges. We create a function display() which takes a list of challenges. But what if we specifically pass in a list of Reverse challenges?

# Create a generic list type using an invariant type variable T.

T = TypeVar('T')

class MyList(Generic[T]): ...

def display(chals: MyList[Challenge]): ...

display(MyList[Reverse]())

# ERROR! Argument 1 to "display" has incompatible type "MyList[Reverse]"; expected "MyList[Challenge]"(N.B. For the sake of this section, I've used a custom MyList type instead of typing.List.)

But why did this error? Although mypy deduced that $\texttt{Reverse} <: \texttt{Challenge}$, it couldn't deduce that our subtype query $\texttt{MyList[Reverse]} {} <:^? \texttt{MyList[Challenge]}$ holds.

This is where covariance and contravariance come into play. With these two bad bois, we can derive further relationships on generic types. The two are similar, with a minor difference.

- Let $F[T]$ be a generic container with type parameter $T$.

- If $T$ is covariant, then $A <: B\ \iff\ F[A] <: F[B]$ for any type $A$, $B$.

- If $T$ is contravariant, then $A <: B\ \iff\ F[A] :> F[B]$ for any type $A$, $B$.2 (It flips!)

- If $T$ is invariant, then $A = B\ \iff\ F[A] = F[B]$. No other subtyping relationships are derived. (This is the default!)

Hence, in the previous code example, we can fix the code by adding covariant=True:

T = TypeVar('T', covariant=True)Now $\texttt{MyList[Reverse]} {} <: \texttt{MyList[Challenge]}$, and the program compiles.

At this point, you should be able to appreciate the double entendre in the title: N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless].

Metaprogramming with Type Hints

We haven't even started digging through output.py! Thankfully, the challenge author linked a paper for our perusal.

Be a Subtype Checker

Back to the challenge. The program leverages the mypy type-checker to perform flag-checking. The last line of output.py asks an important question (aka subtype query): is QRW_s29[L___TAPE_END__[N[...]]] a subtype of E[E[Z]]???

To answer this subtype query, we need to search for a trail of supertypes leading us from the supposed subtype (QRW_s29[L___TAPE_END__[N[...]]]) to the upper type (E[E[Z]]).

A quick aside.

- We use "$\rightsquigarrow$" to denote a resolution step in the checker.

- For convenience, we simplify expressions by ignoring brackets: $C[D[E[A]]]$ becomes $CDEA$.

How does the search go? Meet the two subtyping rules used by the type-checker:

- Super. Substitute a type with its supertype. $$ (C : D) \land (CA <: EB) {} \rightsquigarrow DA <: EB $$ In English, if $C$ has a supertype $D$, we can "go up a level" to search for a match.

- Cancel.3 Remove the outermost type from both sides of the query. (And flip, since all type parameters are assumed to be contravariant!) $$ EA <: EB \rightsquigarrow A <: B $$ This just comes from our definition of contravariance.

The search terminates once we find a match $A <: A$.

What if there are multiple supertypes (due to multiple inheritance)? Wouldn't our paths diverge? Which one do we choose?

Keep in mind we're performing a search.

A good heuristic is to choose a supertype that cancels out the outer type on the other side.

For example:

class C(Generic[T], A["C[T]"], B["A[T]"]): ...

_: B[C[Z]] = C[C[Z]]Here, choosing $BAT$ allows us to cancel $B$ in the next step.

- $CCZ <:^? BCZ$

- $\rightsquigarrow BACZ <:^? BCZ$ (Super)

- $\rightsquigarrow ACZ :>^? CZ$ (Cancel)

Subtype-Checking Example

Let’s walk through an example of an infinite subtyping query.4 Here's the code:

from typing import TypeVar, Generic, Any

z = TypeVar("z", contravariant=True)

class N(Generic[z]): ...

x = TypeVar("x")

class C(Generic[x], N[N["C[C[x]]"]]): ...

class T: ...

class U: ...

_: N[C[U]] = C[T]() # Subtype query: CT <: NCU."C[C[x]]" is quoted in order to forward-reference C. (We declare and use it in the same statement.)

And here's the applied rules:

- $CT <:^? NCU$

- $\rightsquigarrow NNCCT <:^? NCU$ (Super)

- $\rightsquigarrow NCCT :>^? CU$ (Cancel)

- $\rightsquigarrow NCCT :>^? NNCCU$ (Super)

- $\rightsquigarrow CCT <:^? NCCU$ (Cancel)

- (and so on...)

As you may notice, we started with $CT <:^? NCU$, but after 4 steps, another $C$ joined the party. Inductively, this will continue to grow forever (or until mypy runs out of space).

Python Type Hints are Turing Complete

It turns out that Python type hints are Turing Complete thanks to two characteristics: contravariance and expansive-recursive inheritance.

Contravariance, as we saw previously, means $A <: B\ \iff\ F[A] :> F[B]$.

In this section, we assume all type parameters are contravariant.

Expansive-Recursive Inheritance is more complicated to define, but the implications are that we can inherit recursively, and generate infinite, undecidable subtype queries. We saw an example of this in a previous section. (Read more in §2 of Roth's paper.5)

With these, Python type hints can (slowly) simulate any Turing machine or computation!

What is a Turing Machine?

A Turing Machine is a theoretical computing device that operates on an infinite tape divided into cells. It has a read/write head that follows rules to read, write, and move on the tape based on its current state and the symbol it reads. It repeats this process until it reaches a halting state.

Turing Machines are powerful because they can solve a wide range of computational problems. They can perform calculations, simulate other machines, and theoretically solve any problem that can be solved by an algorithm. They serve as a fundamental model for understanding the capabilities and limitations of computation.

Get some intuition by playing the Turing Machine Google Doodle.

The whole ordeal is rather complicated. Essentially, there are two things to be aware of:

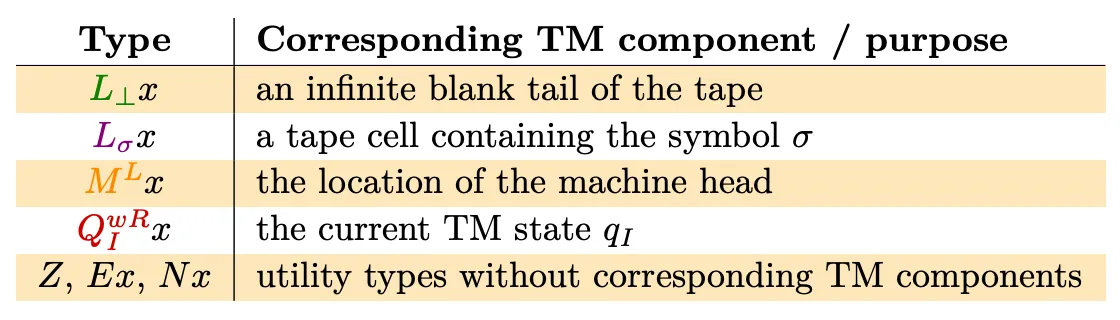

Type Encoding. Different aspects of the tape machine are encoded as types. For example, the

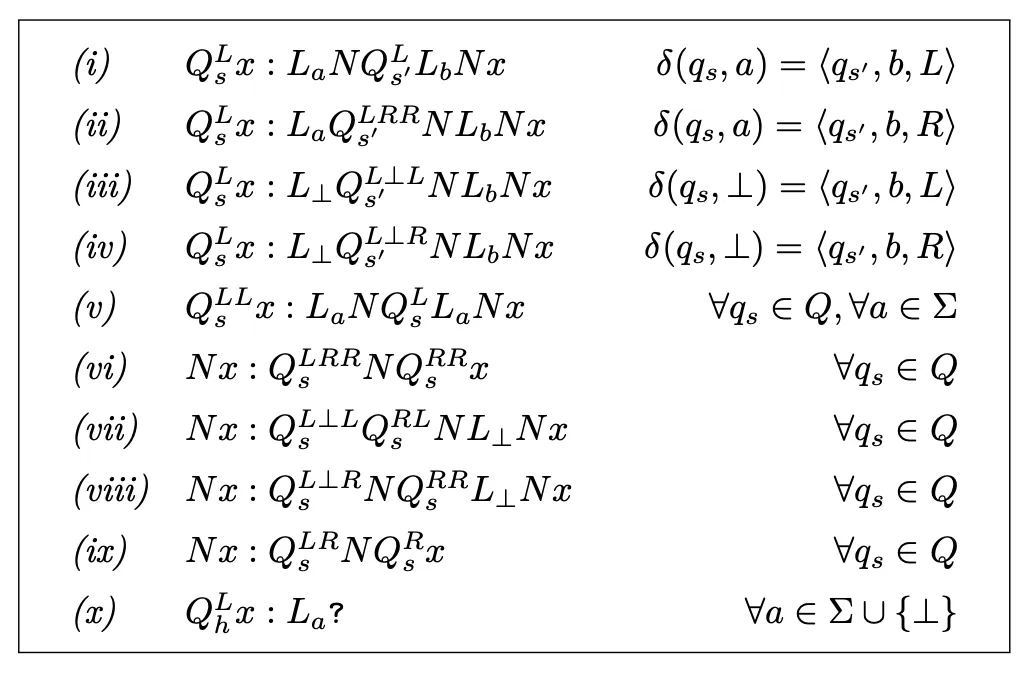

L_*encode the set of possible values (excluding $\bot$, i.e. no value), andMLencodes the machine head.The components of Grigore’s subtyping machine. All classes are parameterised by a contravariant type parameter $x$, except $Z$, which is monomorphic.5

Inheritance Rules. These are used to encode state transitions and the general mechanics of the Turing machine.

Roth's subtyping inheritance rules. This image is included to illustrate inheritance rules. They differ from the rules in the challenge (which are based on Grigore's work). The first 4 rows encode Turing Machine state transitions. Again, the type parameter $x$ is contravariant.5

If you want to read more, I suggest reading §1.2 of Roth's paper.5

Decoding the Challenge's Subtype Query

Just for fun, let's solve some subtype queries from the challenge. Who needs a job when you're employed as a full-time subtype checker?

Although the given subtype query in output.py doesn't work, we can still try simpler versions. It turns out the query recurses on the numbers. For example, the following queries compile:

a: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s71[L___TAPE_END__[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()

b: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s46[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]()

c: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s06[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[L_d[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]]]()

d: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s30[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[L_d[N[L_n[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]()We just started with the base case (empty suffix of flag), and worked backwards.

Let's look closer at the base case:

$$\texttt{QRW\_s71[...]} <:^? \texttt{E[E[Z]]}.$$

It turns out this is a special case, since the declaration of QRW_s71 inherits from E["E[Z]"]. So with just one Super expansion step, we conclude that the base case checks out. Wow, life seems easy as a subtype-checker.

Let's try the next query.

_: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s46[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]()Although QRW_s46 inherits multiple classes, we'll substitute the E["QRL_s46[N[T]]"] supertype, because this allows us to cancel E[...] afterwards.

# Super.

_: E[E[Z]] = E[QRL_s46[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]]]()

# Cancel.

_: QRL_s46[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]] = E[Z]()We can carry on...

_: QRL_s46[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]] = QRL_s46[N[QLW_s46[E[E[Z]]]]]()

_: L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]] = QLW_s46[E[E[Z]]]()

_: L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]] = QLW_s46[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]()

_: MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]] = QLW_s46[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]()

_: L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]] = QLW_s46[MR[N[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()

_: E[E[Z]] = QLW_s46[MR[N[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()Boy, work as a subtype checker seems like slave labour.

Notice that we seem to have... doubled-back? Let's do a quick comparison.

# Initial query.

_: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s46[L___TAPE_END__[N[L_s[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]]]()

# Midway.

_: E[E[Z]] = QLW_s46[MR[N[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()Indeed, the query has made one pass over the tape. Also notice how:

QRW_s46changes toQLW_s46. (Direction swapped!)- The chain of tokens is reversed:

L___TAPE_END__,L_s,MRbecomesMR,L_s,L___TAPE_END__.

This is one shortcoming of Grigore's encoding of a subtyping machine: it makes a pass over the entire tape before processing a single state on the Turing Machine. This drastically increases the runtime of the machine.

Let's continue...

_: QLR_s46[N[MR[N[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]] = E[Z]()

_: MR[N[L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]] = QRW_s46[E[E[Z]]]()

_: L_s[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]] = QR_s46[E[E[Z]]]()

_: L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]] = QRW_s71[MR[N[L_x[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]()

_: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s71[L___TAPE_END__[N[MR[N[L_x[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()Oh look! We've arrived back at QRW_s71! Time for another quick comparison:

# QRW_s71 query (original).

_: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s71[L___TAPE_END__[N[MR[N[L___TAPE_END__[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()

# QRW_s71 query (deduced from QRW_s46).

_: E[E[Z]] = QRW_s71[L___TAPE_END__[N[MR[N[L_x[N[E[E[Z]]]]]]]]]()Looks like L___TAPE_END__ is replaced with a L_x. Eh, still resolves to E[E[Z]] though, so we're fine. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

This was a rather informal attempt at induction, but hopefully it provides some insight on how the subtype query is resolved recursively.

Closing Remarks

Overall, this is a remarkable CTF challenge. When opening the files, I was pleasantly surprised, because it's so rare to see type-theoretic challenges.6 (In fact, this was the first type-theoretic chal I've ever seen!)

I still feel like we cheated the challenge by not going the painstaking, masochistic route of pathfinding the subtype tree. I guess that method would prove more effective if there were more red-herrings (e.g. misleading class inheritances).

But overall, an intellectually challenging reverse challenge!

References

- Roth, Ori. 2023. Python Type Hints Are Turing Complete.

- Good for intuition + explanation of concepts.

- Builds upon Grigore's paper and presents an optimised subtyping machine.

- Grigore, Radu. 2016. Java Generics are Turing Complete.

- The implementation of the CTF challenge was based on this paper.

Footnotes

N.B. Grigore's and Roth's paper use a different notation ($\blacktriangleleft$ / $\blacktriangleright$) for subtype queries, but I opted to use $<:^?$ / $:>^?$ instead. ↩︎

You may be wondering how the heck is contravariance useful. Well, it's immensely useful for functions and serialisers. ↩︎

In the paper, they use Var instead of Cancel, but I think the latter conveys the operation better. ↩︎

Blatantly taken from Roth's paper. ↩︎

Roth, Ori. 2023. Python Type Hints Are Turing Complete. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

I was also slightly disappointed when it turns out the solution was rather straightforward. But eh, it was fun reading the paper. :D ↩︎