AOC 2021 Day 16 – Parser Combinator Fun

Decoding packets with monads.

This post is a writeup on solving the Advent of Code 2021 Day 16 challenge: Packet Decoder.

The Problem

We're given as input a string of hexadecimal characters (0 to F). Our mission? To translate those characters into an expression of packets (part 1) and to then evaluate it (part 2).

Before diving into code, we should first understand the format of the packets, what exactly we need to parse, and what we're looking for. The majority of this section is just me trying to summarise the problem without all the fluff. I'll skip over some things, but if you're confused, just read the full explanation on AOC.

To start off, we're given a bunch of hex characters:

D2FE28To decode the packets, we first need to translate each character into binary (1s and 0s). The above hex string translates to:

110100101111111000101000We can now begin parsing packets. There are two kinds of packets: literals and operators. There is also the notion of sub-packets, meaning a packet can be a child of another packet.

- Literals. The format of literal packets is

VVVTTT[AAAAA]+VVV: 3 bits for the version number.TTT: 3 bits for the packet's type ID. A literal packet will always have type ID 4. Any other type ID is an operator.[AAAAA]+: at least one group of 5 bits. The last group will start with a1.

- Operands. There are two types of operand packets, I'll just call them length-based operand packets and count-based operand packets.

- Length-based operands have format

VVVTTTIL{15}....VVV: as before, these are the 3 bits of version number.TTT: 3 bits of type ID.I: the length type ID. For length-based operands, this is0.L{15}: 15 bits indicating that the nextL{15}(decimal) bits are sub-packets.

- Count-based operands follow

VVVTTTIL{11}....VVV,TTT: ditto.I: the length type ID. For count-based operands, this is1.L{11}: 11 bits indicating the number (or count) of sub-packets.

- Length-based operands have format

(See the AOC explanation for examples.)

Our input would be provided as a single large packet, containing many subpackets (and subpackets within subpackets, etc.). For part 1, we need to sum the version numbers of all packets. For part 2, we need to evaluate the expression of packets. Operand packets have different operations, determined by their type ID.

Solving

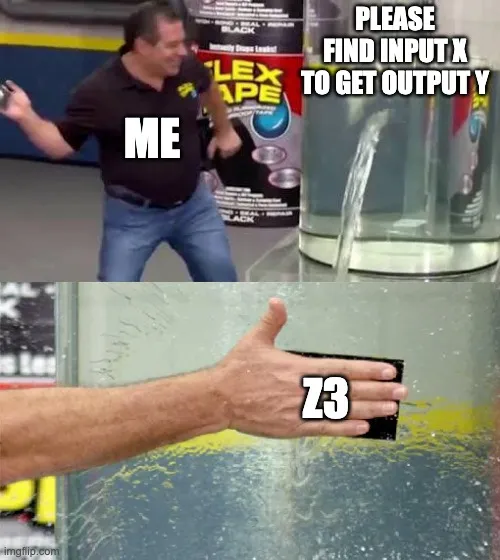

If I were using C++, I might try using bit-fields, some std::bit_cast/std::reinterpret_cast magic, and a couple classes plus inheritance. Sticking to my resolve to use Haskell or Rust, I decided to use parser combinators.

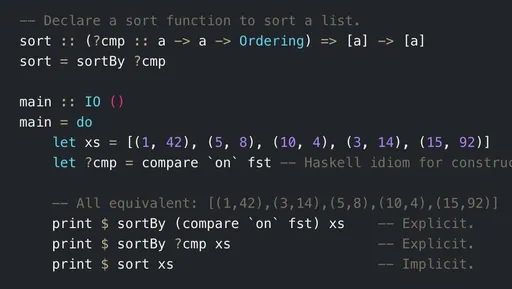

The template I'm using allows me to solve a challenge by writing three functions:

parse :: Parser Packet,part1 :: Packet -> Int, andpart2 :: Packet -> Int.

These will be covered in this post. The driver code of the template (defaultMain) is elaborated in my Haskell utilities post.

Parsing

We'll cover the parse function first, and move towards part1 and part2.

parse :: String -> Packet

parse = subparse packet . concatMap (\hex -> read $ toBinary $ "0x" ++ [hex])

where

toBinary n = printf "%04s" (showIntAtBase 2 ("01" !!) n "")

subparse :: Parser a -> String -> a

subparse p s = case runParser (p <* many (char '0')) "" s of

Right res -> res

Left err -> trace (errorBundlePretty err) undefinedparse takes a hex string, converts it to a binary string and parses it into a packet. The subparse helper takes a parser and the binary as input string and runs the parser (leaving out any leftover '0's). We'll reuse subparse with some differences later on, hence the reason we give it a generic type.

runParser returns an Either type. In this case, it means that it either returns a Right case (denoting success) or Left case (denoting failure).

Data Types

Let's first define the structure of the data we're working with. With Haskell, we can easily define algebraic data types (ADTs) like so:

data Packet = Packet Int Int PacketObj deriving Show

data PacketObj = Literal Int | Operands [Packet] deriving Show- Each

Packettakes 2Ints (the version and type ID), followed by aPacketObj. - The

PacketObjcan be anIntLiteral... - or it could be an operand with a list of packets (

[Packet]).

The data types are like a cornerstone to building our foundation. Without it, we become a bit lost when writing the algorithm. By writing our data types beforehand, we get a concrete idea of how the data is structured and partition, and what we need to do to get from point data A to point data B.

One of the key points in these Packet data structures is that a Packet is a recursive type/object. This allows us the flexibility of recursion (as we'll see later in the part1 and part2 solutions).

Parser Combinators

Usually when parsing text, the traditional solution is to use regex. The problem with regex, however, is that we don't get type information until after compiling, matching, and some extra parsing. Parser combinators are stronger in this regard, being composable and flexible while at the same time providing type information.

Type information may sound a little overrated, but typing is quite useful for catching errors at compile-time and solidifying program logic without being sniped by a RuntimeError later.

We can begin by writing the combinator that will consume n bits.

bits :: Int -> Parser String

bits n = count n digitCharThe bits function takes an integer n and returns a Parser String that consumes that many digitChars. count and digitChar are functions from the parsec library I'm using. bits doesn't exactly consume bits but rather digits (0-9). However, we'll assume that it is fed only bits.

Let's also define a function to convert from a binary string to a decimal (base-10) integer.

fromBinary :: String -> Int

fromBinary = foldl' (\acc d -> 2 * acc + digitToInt d) 0We can then compose fromBinary with the bits parser to parse numbers and convert numbers.

Decoding Literal Packets

Let's use our helper functions to write a parser for literal packets:

packet :: Parser Packet

packet = do

version <- fromBinary <$> bits 3

typeID <- fromBinary <$> bits 3

if typeID == 4

then do

bs <- collectWhile (bits 5) $ \(b : _) -> b == '1'

return $ Packet version typeID $ Literal $ fromBinary $ concatMap (drop 1) bs

else do

{- -- code for operand packets -- -}

where

collectWhile p f = do -- Parse while condition is true.

x <- p

if f x then (x :) <$> collectWhile p f else return [x]Hopefully the majority of the code above is readable.

- We first parse 3 bits of version and convert it to a decimal

Int. - Then 3 bits of type ID and also convert to a decimal

Int. - Next, we check the packet's

typeID. If it's4, then it's a literal packet. - We then try parsing the

PacketObjfor literal packets: keep parsing groups of 5 bits until the group starts with a'1'. - Now we have a list of 5-bit groups stored in

bs. - The next line goes through the process of converting the bits into a single

Intand wrapping it as aPackettype. - The explanation for

collectWhile... is left as an exercise for the reader.

Hoof- That was quite long-winded. But you can see how type information is being passed around. version and typeID are Ints, because we parsed them from binary strings. We can now do Inty things with them, e.g. comparison, just like typeID == 4 in the code above.

We're also confident that we've covered non-Int edge cases because the parser engine and Haskell's type system will report it for us; and so if the parsing succeeds, we know that our data isn't a string, character, boolean, or monkey. We assumed there won't be out-of-bound issues since AOC usually constrains numbers to 32/64-bit ints. But if the need arises, we could always upgrade from Ints to Integers (which are Haskell's equivalent of dynamically-sized integers).

Decoding Operand Packets

For operand packets, let's define another parser helper for parsing subpackets. We'll take as argument an Int (the length type ID) and return a parser that parses a list of (sub)packets.

operands :: Int -> Parser [Packet]

operands 0 = do -- Length type ID == 0 ---> length-based operand

len <- fromBinary <$> bits 15

subparse (some packet) <$> bits len

operands 1 = do -- Length type ID == 1 ---> count-based operand

num <- fromBinary <$> bits 11

count num packetPretty straightforward. For length-based operands: parse the length, then parse 1 or more packets out of the next length bits. Count-based operands are even more straightforward: parse the expected number of subpackets, then parse the num packets.

In both cases, subpackets are parsed by recursing to the packet parser, which we can now finish:

packet :: Parser Packet

packet = do

version <- fromBinary <$> bits 3

typeID <- fromBinary <$> bits 3

if typeID == 4

then do

{- -- code for literal packets -- -}

else do -- Code for operands.

lenTypeID <- fromBinary <$> bits 1

children <- operands lenTypeID

return $ Packet version typeID $ Operands children

where

...Also pretty straightforward. We've added three lines of code for parsing the operand case. I think this warrants no explanation and should be a simple exercise for the reader. :)

Part 1

Summing the version numbers should be no problem, and knowing where are versions are and that they're already Ints, a simple recursion with sum and map should do it:

part1 :: Packet -> Int

part1 (Packet v _ obj) = case obj of

Literal _ -> v

Operands ps -> v + sum (map part1 ps)Part 2

Part 2 is more complicated, but only slightly. Essentially, each type ID other than 4 corresponds to some operation. 0 is addition, 1 is multiplication, 5 is >, and so on.

part2 :: Packet -> Int

part2 (Packet _ op obj) = case obj of

Literal x -> x

Operands ps -> case op of

0 -> sum

1 -> product

2 -> minimum

3 -> maximum

5 -> \[a, b] -> if a > b then 1 else 0

6 -> \[a, b] -> if a < b then 1 else 0

7 -> \[a, b] -> if a == b then 1 else 0

$ map part2 psAnd that's it. Tada! Welcome to the wonderful magic of parser combinators.

Full Script

For completeness, here's the full D16.hs script. This uses my Haskell Utils module, and the actual main function is placed in another file. The background work is done there so that here we could focus on the process of getting from input (String) to output (Int) here.