SEAL

Some Extensions for the Amy Language – a programming language project made with Scala.

This project was part of a course on compiler design and is published online along with a report. This post provides a little background and summary about the project and also introduces some concepts at a basic level.

Synopsis

Amy is a dumbed-down version of Scala. It inherits most of Scala's basic features:

- Basic types (limited to

Int,Boolean,String,Unit) plus literals (numeric literals,true/false, string literals,()for unit) - Integer and boolean arithmetic with the usual operators

- String concatenation with

++ - Pattern matching using

match valbindings (immutable variables)if/else- Functions

- Modules (but without

importmachinery) - Custom algebraic data types using

abstract classandcase class

(See the Amy Specs for more details.)

The idea of the project is to extend the Amy compiler which we have built during the course labs. The main compiler pipeline we worked with was:

- Lexing (grouping characters into tokens)

- Parsing (going from a list of tokens to an abstract syntax tree (AST))

- Name analysis (linking name symbols to their declarations)

- Type checking (ensuring the programmer isn't stupid and knows what they're doing, checks for consistency and "soundness" of types)

- Code generation (translate the AST to efficient low-level assembly code, we used web assembly in this course)

- Interpret (an alternative to code gen)

Extensions

As I enjoy functional programming, so my extensions mainly focus on extending types and functions.

Built-in Tuples

SEAL supports tuples and typechecking tuples.

(1, 2); // Construct a tuple.

val t: (Int, Int) = (3, 4); // Tuple types.

t(0); // Access a tuple -- returns 3.

t match {

case (x, y) => ... // Pattern match on a tuple.

};Tuples are generally useful as anonymous structs/record types, when you want groups of data without the hassle of naming. Most modern languages today have tuples built into the type system. C++ has tuples, but they are sadly wrapped in a verbose library.

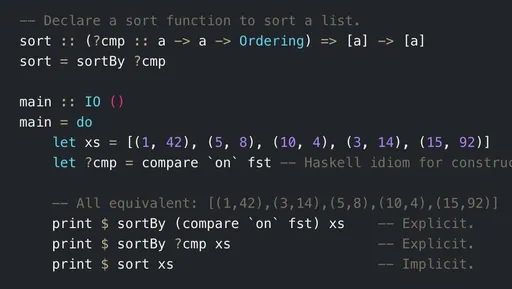

Higher Order Functions and Friends

SEAL also supports higher order functions, including function types, lambdas, and currying. These days, most languages support passing functions around as first class citizens to enable more abstract logic and avoid duplication of code. I'll explain all these big words in a bit.

def operate(f: Int => Int): Int => Int = { // Function types.

\(x: Int) -> f(x) // Lambda.

}

// `operate` is a higher order function since it takes in a function as parameter.

val inc: Int => Int = operate(\(x: Int) -> x + 1);

inc(0); // 1

inc(1); // 2

operate(\(x: Int) -> x * 5)(6); // Currying -- returns 30.Higher Order Functions

In programming, a function takes values as parameters. Typical values are integers, floats, strings, characters, arrays. Most programming languages nowadays also treat functions as values, such that we can pass them to (other) functions. One common example is the map function. Here is a simplified version for integers:

def map(f: Int => Int, xs: Seq[Int]): Seq[Int] = {

for (x <- xs)

yield f(x)

}

def plus1(x: Int): Int = {

x + 1

}

assert(map(plus1, Seq(1, 2, 3)) == Seq(2, 3, 4))(SEAL doesn't support the code above but Scala does. This code is for demonstration purposes only.)

Here, map takes a function f as a parameter (thus map is a higher order function). Then it applies a function f to every element x in a sequence xs and returns a new sequence with those new elements.

In the example above, we apply plus1 to each element in Seq(1, 2, 3), and this leaves us with Seq(2, 3, 4).

Lambdas

The idea of a lambda is a function with no name. With higher order functions, sometimes the inner functions are only used once and thrown away. For example:

def plus1(x: Int): Int = { x + 1 }

def plus2(x: Int): Int = { x + 1 }

def plus5(x: Int): Int = { x + 1 }

map(plus1, Seq(1, 2, 3))

map(plus2, Seq(1, 2, 3))

map(plus5, Seq(1, 2, 3))Instead of declaring multiple functions with verbose syntax, we can use a shorthand:

map(x => x + 1, Seq(1, 2, 3))

map(x => x + 2, Seq(1, 2, 3))

map(x => x + 5, Seq(1, 2, 3))The resulting code is more concise. All modern programming languages have lambdas, except the esoteric ones.

The challenge with implementing lambdas comes during name analysis. Lambdas have a notion of "capturing" outside variables. So how do we implement this? SEAL uses closure conversion. See section 3.1.1 of the report for details.

Currying

The idea of currying is grounded in mathematics and computer science. But in programming, currying can be thought of as applying a function multiple times, and each time you apply an argument, you get back a new function. Allow me to demonstrate with an example:

def f(x: Int)(y: Char) = {

println("int: " + x + "; char: " + y)

}

f(1)('a') // int: 1; char: a(SEAL doesn't support declaring curried functions, but allows you to declare a function which returns a function, providing the same effect as currying. The above code compiles with Scala.)

Confused with the above example? It helps to study the type of f, which is f: Int => Char => Unit. (Unit here just means we return nothing, similar to void in C/C++.)

If we apply an argument (1) to f, we have the type f(1): Char => Unit, which is a new function. Now we can actually do whatever we like with it. For example, we could save it in a variable and call it multiple times:

val g = f(10000000) // g: Char => Unit

g('b') // int: 10000000; char: b

g('c') // int: 10000000; char: c

g('d') // int: 10000000; char: dAnd that's why currying is pretty useful: because it makes partially applied functions easy to write and use.

Extended Standard Library

SEAL also introduces additional functions in its standard library to conveniently work with IO, Strings, randomness, etc.

File.open(filename: String): Reader-- Opens a file and returns a reader object. Errors if file can't be opened.- Read functions -- Functions for reading lines and tokens.

File.readLine(file: Reader): StringFile.readString(file: Reader): StringFile.readInt(file: Reader): IntFile.readBoolean(file: Reader): Boolean

File.isEOF(file: Reader): Boolean-- Checks if a file has hit EOF.String.equals(a: String, b: String): Boolean-- For comparing strings.Random.int(n: Int): Int-- Generates an integer between 0 inclusive andnexclusive.Random.range(min: Int, max: Int): Int-- Generates an integer betweenminandmaxboth inclusive.Random.oneIn(n: Int): Boolean-- Picks a number between 0 inclusive andnexclusive, and returns true if you're lucky.

![Thumbnail for N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]](/img/posts/programming/concepts/assets/thumbnail-512w.webp)