HKCERT CTF 2023 – Decompetition: Vitamin C++

A beginner-friendly writeup to reverse-engineering C++. Years of complex shenanigans condensed!

Oh boy, another C++ reverse challenge. :rubs_hands_in_delight:

Decompetition: Vitamin C++ is a reverse engineering challenge in this year's HKCERT CTF, an annual online capture-the-flag competition hosted in Hong Kong. The format is slightly different from usual rev chals in that we’re required to derive the source code of a binary. This really tests our understanding of how the language is compiled into machine code.

So whether you’re a first-timer or a veteran at reversing C++, this is a fun(?) way to dive deep into or review neat aspects of the language.

If you want to follow along, you can grab the challenge here: GitHub (Backup). I’ll also be relying on Ghidra as my decompiler, because I am poor want to support open-source.

Description

Author: harrier

4/5 stars ⭐️. 5/311 solves.

So let's learn reverse with Decompetition!1 The goal is simple: try to recover the original source code as much as possible, while understand the code logic deeply to get the internal flag! Only with two of those together, you will win this flag.

STL is used everywhere, so it would be nice to be able to reverse them!

Note there is an internal flag with flag format

internal{}. Please do not submit this directly to the platform.g++ version: g++ (Debian 12.2.0-14) 12.2.0

nc chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk 28157

And a note on testing:

If you want to run this locally, you can install all the prerequisite library with

pip, and runpython compiler trie.disasm.pip install pyyaml capstone intervaltree pyelftools diff_match_patch

Thus, to get the flag, we need to:

- Obtain the source code (97.5% similarity).

- Obtain the internal flag by reversing the source code.

- Submit the internal flag (not to the platform, but to the remote connection).

- Profit!

(You can see this process play out in compiler.py.)

The first step is the most challenging. Even if we have a decent understanding of the program, we still need the source code to continue.

Let’s start by analysing what we’re given and how we can approach the problem. We'll aim for 100% similarity, but go step by step.

Analysis

Unzipping our bag of goodies, we’re given:

- compiler.py. This is the backend doing all the compilation and diffing.

- Only

TrieNodemethods,wordhash, andmainare diffed. - Prior to compiling, our code is prefixed with some boilerplate (includes of

unordered_map,string, andiostream).

- Only

- build.sh. Checks our code against bad patterns, and compiles the program.

- trie. This is the binary file of our target source code. Open this in your favourite decompiler.

- trie.disasm. This is the disassembly used by compiler.py for diffing.

- flag.txt. Read and printed by compiler.py after submitting the internal flag.

- A bunch of other Python files to make things work.

Is there a way we can simplify the process?

Inline assembly with asm, attribute trickery, and macros are disallowed.

A quick Google search for TrieNodes resulted in disappointment. The mix() function is especially unique, as tries generally just do insert/search. So we can probably conclude: the implementation was either hand-spun or modified substantially.

It appears the most productive approach is to tackle the problem head on.

But hey, it’s just a simple lil’ trie, not a friggin standard template container or Boost/Qt library. We can do this!

Trie Me

Let’s briefly review tries. What is a trie?

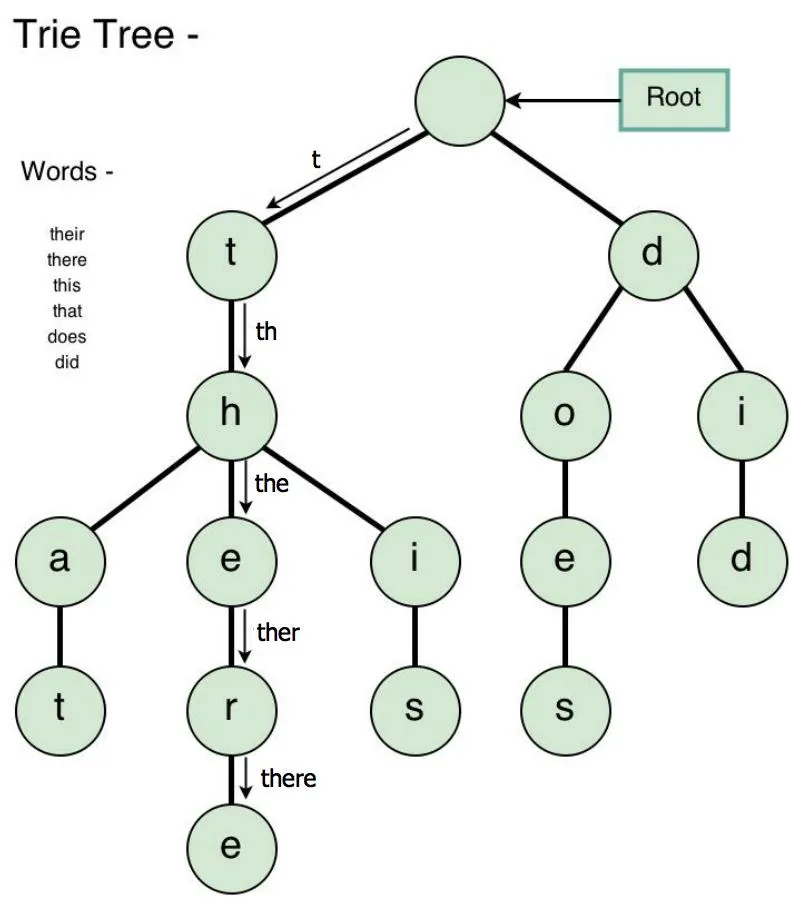

Tries, or prefix trees, are data structures commonly used to efficiently store and retrieve strings. They are particularly useful for tasks like autocomplete or spell checking. The key idea behind tries is that each node in the tree represents a prefix of a string, and the edges represent the characters that can follow that prefix.

Example of trie containing the words that, there, this, does, and did. Each edge represents a letter to the next prefix. (Source)

Example of trie containing the words that, there, this, does, and did. Each edge represents a letter to the next prefix. (Source)

- In terms of matching an exact string, the complexity is similar to a hashmap:

O(n)insert/search time, w.r.t. the length of the string. But a hashmap is typically faster as it requires fewer operations. - The power of tries comes with alphabetical ordering and prefix search (which is why they’re useful for autocomplete). Hashmaps can't do this.

Setting Up the Structure

Demangling Names

Let’s start by demangling functions! This way, we’ll roughly know its name and signature—big clues, from a functional viewpoint.

In C++, function and class names are mangled. So instead of using sensible names like TrieNode::mix, std::string::substr, and std::endl, the compiler stores hellish sequences like _ZN8TrieNode3mixEc, _ZNKSt7__cxx1112basic_stringIcSt11char_traitsIcESaIcEE6substrEmm, and _ZSt4endlIcSt11char_traitsIcEERSt13basic_ostreamIT_T0_ES6_. (Yes, endl is a function.)

Why do C++ compilers behave this way?

This has to do with function overloading. For example:

void print(int i) { /* ... */ }

void print(float f) { /* ... */ }

void print(std::string s) { /* ... */ }C++ function overloading in action. Same name. Different parameters.

With function overloading, names are reused. Now if the names are the same, how can the linker find and call the right function? The compiler solves this by encoding a function’s signature into its name, so that all names are unique. (We don't have this problem in plain old C, because function overloading isn’t even a concept!)

To demangle these cryptic monstrosities, we can throw them into online tools (e.g. demangler.com) or just use a C++-enabled decompiler (e.g. Ghidra) which automatically demangles names.

Classy Types

When discussing C++, it’s hard to avoid the topic of classes. These supercharged C-structs are the basis of any object-oriented program.

Looking at the demangled function names, we can identify the TrieNode class. What next?

There are two parts to reversing a class:

- Methods/functions. How does the class behave? What does it do?

- These are easy to find due to the prefix (e.g.

TrieNode::). Reversing their content is a different question, which we'll address in upcoming sections.

- These are easy to find due to the prefix (e.g.

- Members. What comprises a class? What is its state?

- This is a tricky question to answer, as variable names are usually stripped. Careful analysis of reads/writes is required (xrefs are useful!).

- Is it set to only 0 or 1? And used in conditions? Probably a boolean.

- Is it compared to other numbers a lot and used near loops? Probably an integer representing size.

- By peeking at the

TrieNodeconstructor, we figure out thatTrieNodehas three members.- An unordered map (aka hashmap) from chars to nodes. Size: 0x38 bytes. As this resembles the edges of the node, we'll call variable this

next_node. - A bool. Size: 1 byte.

- Another bool. Size: 1 byte.

- An unordered map (aka hashmap) from chars to nodes. Size: 0x38 bytes. As this resembles the edges of the node, we'll call variable this

- This is a tricky question to answer, as variable names are usually stripped. Careful analysis of reads/writes is required (xrefs are useful!).

Overall, our structure should resemble:

using namespace std; // FYI, this is discouraged in actual software engineering: https://stackoverflow.com/q/1452721/10239789.

void wordhash(string s) {} // return type: ???

struct TrieNode {

// Members.

unordered_map<char, TrieNode*> next_node;

bool bool1;

bool bool2;

// Constructor.

// Initialise variables. `next_node`'s constructor is called automatically.

TrieNode() : bool1{false}, bool2{false} {} // Member Initialiser List: https://cplusplus.com/articles/1vbCpfjN/

void insert(string s) {} // return type: ???

void search(string s) {} // return type: ???

void mix(char cmix) {} // return type: ???

}

int main() {}Return types are unknown, because most compilers don't mangle them with the name. For now, they've been substituted with void and left as an exercise for the reader.

On Struct vs. Class

Structs are public by default. Classes are private by default.

Public/private are concepts which fall under OOP encapsulation. With encapsulation, we bundle data and only expose certain API methods for public users, whilst hiding implementation. With a cyber analogy, this is not unlike exposing certain ports (HTTP/HTTPS) on a machine, and protecting other ports with a firewall.

I chose to use struct here because I'm lazy and want to make members public.2 Some of them are accessed directly in main anyway.

Read more:

Reversing

Plagiarise a Decompiler

Now that we have a basic structure set up, it's time to dig deeper. We need to go from binary to source code. Hmm… that sounds like a job for… a decompiler!

So let’s start with that! We can plagiarise copy output from Ghidra and rewrite it to make programmatic sense.

Exercise: Reverse the wordhash function.

Solution

char wordhash(string s)

{

char hash = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < s.size(); i++)

hash ^= s[i];

return hash;

}This is a simple hash function which xors all characters in a string. It's not a very effective hasher, because it's prone to collisions (also it's not const-correct). But eh, this is just for a CTF challenge.

Implement the Data Structure

Time to implement the core of the program: the TrieNode class. As before, we can refer to Ghidra's output.

Exercise: Reverse TrieNode::insert, TrieNode::search, and TrieNode::mix.

- We can make good use of Ghidra's Rename, Retype, and Edit Function Signature tools to clean up the code.

- Ghidra sometimes loads incorrect function signatures (e.g. for

operator[]). You may wish to edit the signature so that it displays arguments properly.3

I'll leave the first two functions as an exercise for the reader. :)

mix() seems to be a total oddball, as tries don't usually have such a function.

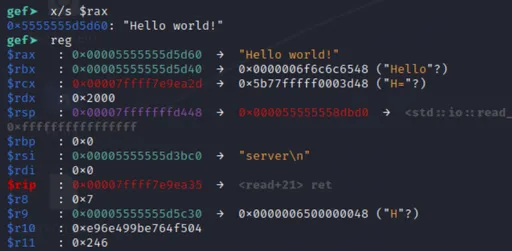

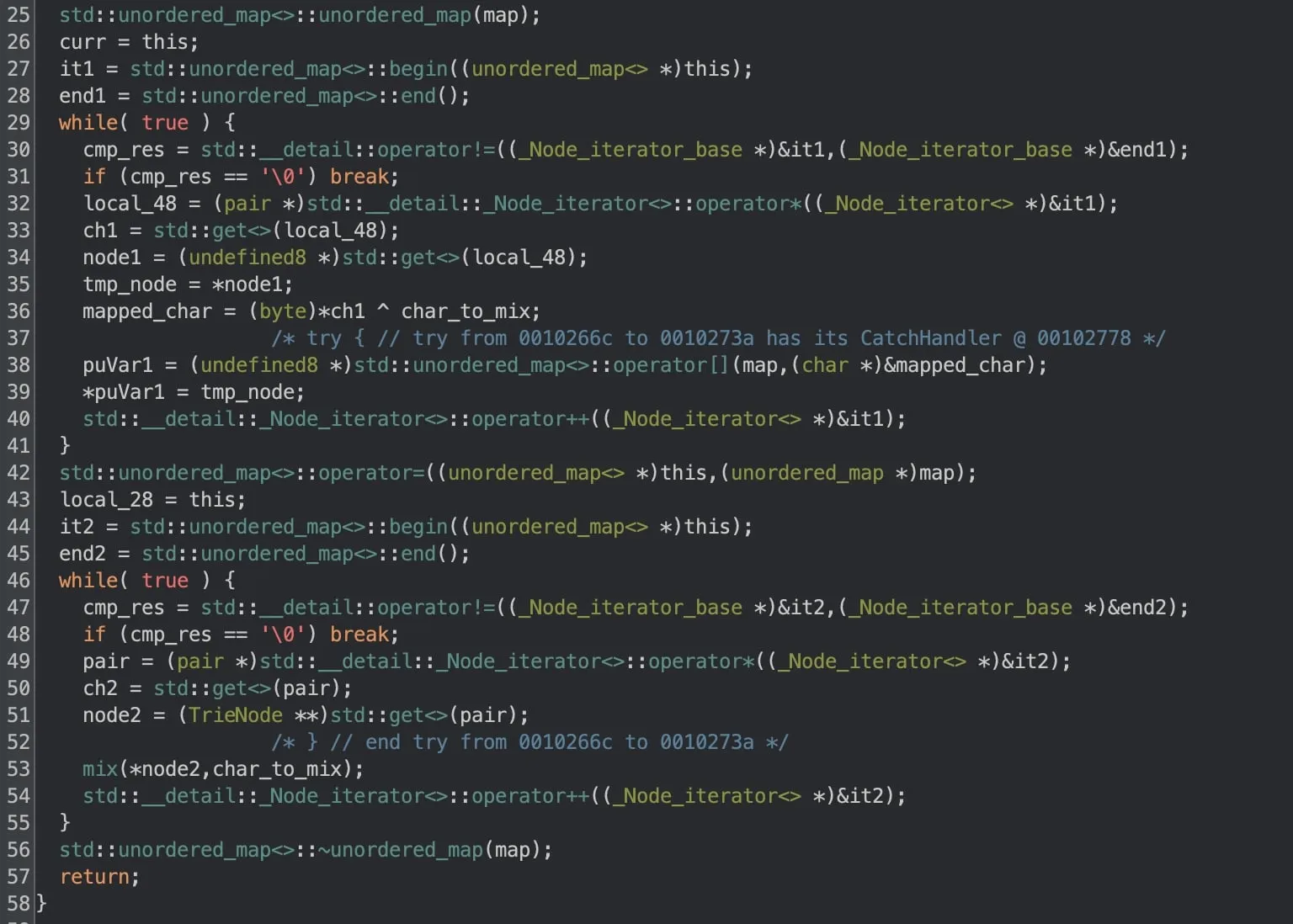

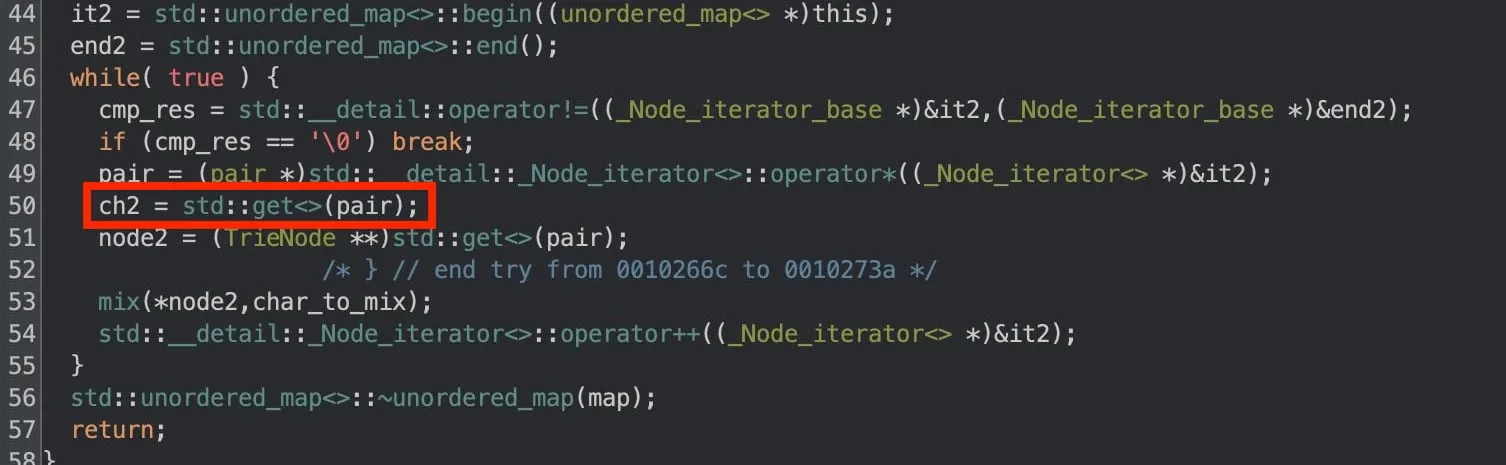

Ghidra decompilation of

Ghidra decompilation of TrieNode::mix().

TrieNode::mix: Possible Solution

void mix(char cmix)

{

unordered_map<char, TrieNode*> new_map;

// For each edge...

for (auto it = this->next_node.begin(); it != this->next_node.end(); ++it) {

auto pair = *it;

char ch = std::get<0>(pair);

TrieNode* node = std::get<1>(pair);

// ...update the character.

new_map[ch ^ cmix] = node;

}

// A new map is used so that old mappings aren't kept.

// Update the map of the current node.

this->next_node = new_map;

// Recurse into child nodes with the same xor key.

for (auto it = this->next_node.begin(); it != this->next_node.end(); ++it) {

auto pair = *it;

char ch = std::get<0>(pair);

TrieNode* node = std::get<1>(pair);

node->mix(cmix);

}

}Now if you run this through the compiler diff, it should respond with some lines:

- call _ZSt3getILm0EKcP8TrieNodeERNSt13tuple_elementIXT_ESt4pairIT0_T1_EE4typeERS7_

+ call _ZSt3getILm0EKcP8TrieNodeERKNSt13tuple_elementIXT_ESt4pairIT0_T1_EE4typeERKS7_

Subtle. But there is a good reason why this occurs. We'll look at this in more detail later.

On Various Features

Common, but worth mentioning.

On auto

auto is a special keyword introduced in C++11 typically used to tell the compiler: "figure out this type for me".

It has seen wide adoption and growing support in the standard (more features for auto are added each standard). Now (C++20) it's used widely in template parameters and lambda parameters.

On Iterators

The previous solution for mix() made use of iterators. These are commonly used by the STL, providing a generic interface for iterating over containers.

for (auto it = container.begin(); it != container.end(); ++it) {

// ...

}We generally start with .begin() and iterate with prefix increment (++it) until we hit the .end() iterator. With iterators, we can apply generic algorithms on generic containers.

On Unordered Map

You may be wondering: why std::unordered_map? Why not std::map? Why type 10 extra keystrokes?

The reason is time complexity.

std::mapis a binary search tree, givingO(log n)search time on average (wherenis the number of entries).std::unordered_mapis a hashmap, givingO(1)search time on average. Takes more space though.

As the value of n increases, the number of operations required for std::map will increase at a faster rate compared to std::unordered_map. This is because std::unordered_map is not affected by the number of entries in the map (except in the case of rehashing); hence, the constant time complexity, O(1).

In the interest of performance, it's typical to opt for unordered_map.

But in our case, since a node only has 256 possible edges (char), the potential speed boost is limited, and the choice between map and unordered_map is debatable. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

On Scoping

An object in C++ has a constructor and destructor, functions that run at the beginning and end of its lifetime. The object's scope affects the placement of its constructor and destructor.4

Let’s look at some examples:

// String in outer scope.

int main()

{

std::string s; // <- string constructor called

if (1) {

// do stuff

}

} // <- string destructor called// String in inner scope.

int main()

{

if (1) {

std::string s; // <- string constructor called

// do stuff

} // <- string destructor called

}Do you C the difference?

Things become complicated when we further consider lvalues and rvalues (think: variables and temporaries).

Complicated Examples

// Passing lvalue string to normal parameter.

// Copy constructor is called and a temp object is created.

void print(string s);

int main()

{

std::string s; // <- string constructor called

if (1) {

// do stuff

// ---

// <- string copy constructor called (copies s to a temporary)

print(s);

// <- string destructor (of temporary string) called

// ---

// do more stuff

}

} // <- string destructor called// Passing rvalue string to normal parameter.

// Regular constructor is called and a temp object is created.

void print(string s);

int main()

{

if (1) {

// do stuff

// ---

// `const char*` literal is implicitly converted to std::string.

// <- string constructor called (creates a temporary)

print("Hello world!");

// <- string destructor (of temporary string) called

// ---

// do more stuff

}

}I don't intend to cover every single possible case. But yes, C++ is extremely nuanced in this regard. (See also: classes, special member functions, move semantics.)

The point is: object scoping is all reflected at assembly level. We can get a good understanding where an object is declared by paying attention to its constructors and destructors.

This applies to classes, such as STL containers. Primitives (int, char, pointers) don't have constructors/destructors, so it’s trickier to tell where they're instantiated. It's even trickier with heavy optimisations.

Exercise: Reverse the main function.

- Use the position of constructors and destructors to determine the scope of various strings.

- Beware backslashes in the inserted strings.

Possible Solution

int main()

{

int opt;

string str;

TrieNode* node = new TrieNode();

// `const char*` literal is implicitly converted to std::string.

node->insert("\x72\x50\x54\x52\x73\x66\x51\x5a\x79\x72\x75\x4b\x7f\x4e\x4d\x55\x47\x7e\x68\x7e\x72\x51\x42\x71");

// node->insert(string("...")); also works

// -- snip --

// node->insert("...");

node->should_mix = true;

cout << "Enter [1] for insert string" << endl;

cout << "Enter [2] for search string" << endl;

while (true) {

cout << "Option: ";

cin >> opt;

if (opt == 1) {

cout << "Input string to insert: " << endl;

cin >> str;

node->insert(str);

} else if (opt == 2) {

cout << "Input string to search: " << endl;

cin >> str;

bool res = node->search(str);

if (res)

cout << "String " << str << " exists." << endl;

else

cout << "String " << str << " does not exists." << endl;

} else {

cout << "Bye" << endl;

return 0;

}

}

}From here on, we'll continue making incremental adjustments to improve our score, while learning various C++ nuances and features.

On Structured Bindings

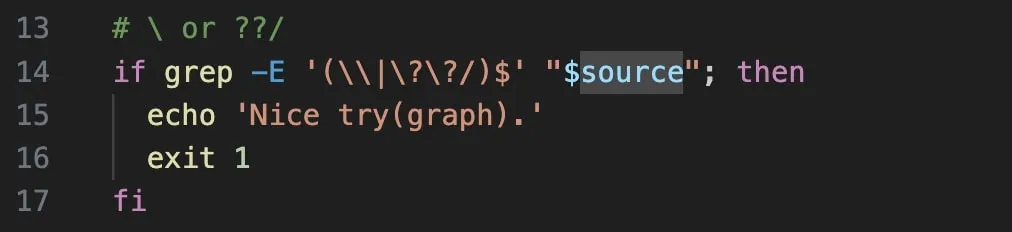

Here we take a detour to peek at build.sh. And something sparkly catches our eye:

g++ "$@" -fno-asm -std=c++17 -g -o "$binary" "$source"Our code is compiled with C++17—what an oddly specific standard!

One cool feature introduced by this standard is structured bindings, which is as close as we can get to Python iterable unpacking.

for (auto it = next_node.begin(); it != next_node.end(); ++it) {

- auto pair = *it;

- char ch = std::get<0>(pair);

- TrieNode* node = std::get<1>(pair);

+ auto [ch, node] = *it;

new_map[ch ^ cmix] = node;

}

Since it is an iterator over key-value pairs, we can dereference, then bind (unpack) the pair to ch and node.

One telltale sign of structured bindings is in the second loop of TrieNode::mix(). Notice how the first item of the pair (ch2 = std::get<0>(pair);) is read but never used.

Ghidra decompilation of the second loop of mix(). Notice how ch2 is never used. (You can also verify this by inspecting the disassembly!)

Another giveaway is that std::get is rarely used to access map pairs, unless in generic code. The idiomatic ways are:

std::pairmembers (through iterator):it->first,it->secondstd::pairmembers (through pair):for (const auto& pr : map) { // pr.first, pr.second }- structured bindings (since C++17)

N.B. With optimisations, these indicators would be less obvious. Thankfully the program wasn't compiled with optimisations.

On Const Ref

We're still short of our target though. Some diff lines stand out:

// Extra stack variables!

- sub rsp, 0xc8

- mov [rbp-0xc8], rdi

+ sub rsp, 0xb8

+ mov [rbp-0xb8], rdi

// Calling the wrong overload!

- call _ZSt3getILm0EKcP8TrieNodeERNSt13tuple_elementIXT_ESt4pairIT0_T1_EE4typeERS7_

+ call _ZSt3getILm0EKcP8TrieNodeERKNSt13tuple_elementIXT_ESt4pairIT0_T1_EE4typeERKS7_

Extracted diff lines from compiler.py output. Red (-) indicates extra lines in our program. Green (+) indicates missing lines.

- Looks like we declared 16-bytes of extra stack variables.

- Local variables are stored on the stack, which allocates memory by a simple

subinstruction. - Larger subtraction = more stack memory allocated.

- Local variables are stored on the stack, which allocates memory by a simple

- It also looks like we called the wrong overload. The mangled names roughly translate to:

// simplified for readability - std::get<0>(std::pair<char, TrieNode*>&) + std::get<0>(std::pair<char, TrieNode*> const&)

We can fix both these issues by qualifying our binding as const&.

for (auto it = next_node.begin(); it != next_node.end(); ++it) {

- auto [ch, node] = *it;

+ const auto& [ch, node] = *it;

new_map[ch ^ cmix] = node;

}

With auto, our binding was creating new char and TrieNode* copies. (Hence, the extra 16 bytes.) With const auto&, we take a constant reference.

- Constant: meaning we only read the value. No modifications. This fixes the second issue.

- Reference: meaning we refer (point) to the original objects instead of copying them. This fixes the first issue.

Using const-refs is good practice for maintainability and performance (imagine copying a 64-byte struct each iteration 🤮).

On For-Range Loops

The astute may notice the above can be refactored slightly with the help of range-based for-loops. These were introduced in C++11, and are like Python for-in loops, but less powerful.

Example

- for (auto it = next_node.begin(); it != next_node.end(); ++it) {

- const auto& [ch, node] = *it;

+ for (const auto& [ch, node] : next_node) {

new_map[ch ^ cmix] = node;

}

In fact, range-based for-loops are syntactic sugar for the plain loops we all know and love.

for (range_decl : range_expr) {

/* ... */

}translates to...

{

auto&& __range = range_expr;

auto __begin = begin; // Usually std::begin(__range)

auto __end = end; // ...and std::end(__range).

for (; __begin != __end; ++__begin) {

range_decl = *__begin;

/* ... */

}

}(See more: cppreference.)

On Control Flow

Decompiler output may not accurately present the control flow of the original program. Changing:

- the order of control flow, and

- which statement is used

may lead us closer to 100%.

Would it make more sense to use a switch instead of an if in a certain place?

Other Useful Tips

- Use Godbolt’s Compiler Explorer to play around with disassembly output. It helps with analysing small details such as variable declaration.

- Remember to set x86-64 gcc 12.2 and

-std=c++17.

- Remember to set x86-64 gcc 12.2 and

- Two good sources for standard library documentation are cppreference (high quality) and cplusplus.com (beginner-friendly).

- Version control is incredibly useful for tracking incremental changes.

The Infernal Flag

Once we recover enough source code, it's time to find the internal flag. This is probably the least interesting part (for me), so I'll keep it short.

Notice:

- In

main, a bunch of garbage strings are inserted into the trie. - Afterwards, mixing is turned on (

node->should_mix = true), so that the nextnode->insert()will jumble the trie...

Now it's time to take a really close look at mix().

- What is jumbled? All the strings.

- How? All chars are xor'ed with a char (the

wordhashof a string). - How many possible chars are there? 256.

- Two words: brute force.

Maybe one of the strings just happens to be the internal flag xor'ed. Who knows?

After getting ≥ 97.5% similarity and finding the internal flag, submit both to the platform and profit!

Final Remarks

I'm sure the chal is called Vitamin C++ because it's designed to make us (mentally) stronger. Every time you trie harder, you lose a brain cell but strengthen a neuron. Indeed, we covered quite a lot of concepts today:

- Language Features:

auto, structured bindings, for-range loops, const-ref. - Library Features: iterators, unordered map.

- Unordered map is preferred for performance in lookup.

- Scoping (and lvalue-rvalueness) affects position of constructors/destructors. (Very good takeaway for C++ reversing.)

- Pay attention to groups of

subandmovinstructions to check if we declared too little/many stack variables. - Ghidra is pretty powerful.

- C++ is fun.

Lots of tuning was involved; but the various tricks employed above netted us a first blood, so I can't complain. Despite a couple lines of janky const-uncorrect code, it was a nice challenge.

Also, who doesn't like a good pun hidden in a challenge?

Solve Sauce

(Files not embedded, as they're a bit big.)

- rev.cpp: Fully reversed (100% similarity) source.

- solve.py: For cracking the internal flag.

- send.py: Driver program to test rev.cpp.

Flag

hkcert23{c++stl_i5_ev3rywh3r3_dur1ng_r3v}Footnotes

Decompetition is a reverse-engineering CTF held irregularly. ↩︎

In proper engineering, we would hide the implementation behind

private, sonext_nodeshould be a private variable. But since this is a CTF, proper engineering comes second. 😛 ↩︎Or just read the assembly and follow the call conventions (thiscall for member functions, fastcall for everything else). ↩︎

This also depends on optimisations, and whether the object contains any other classes. In some cases, constructors or destructors may be inlined or optimised away. ↩︎

![Thumbnail for N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]](/img/posts/programming/concepts/assets/thumbnail-512w.webp)